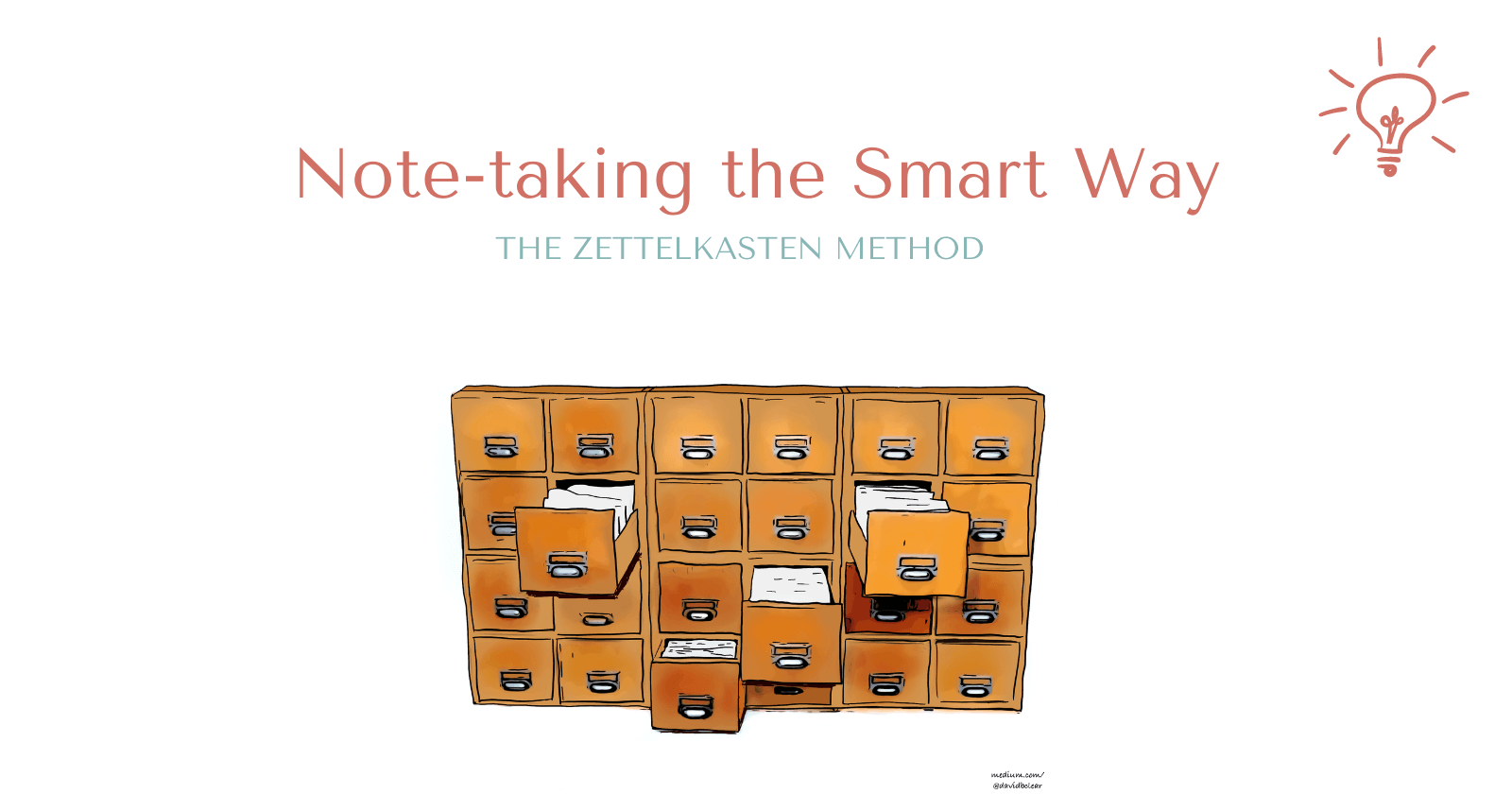

The Zettelkasten Method: Note-taking the Smart Way

For a long time, I considered note-taking a necessary evil. For me, notes were a sketchy record of lessons, a source of study, and a means to a single end: a grade. These notes ended up in the bin at the end of the semester.

I read about subjects that interested me alongside formal education. The list of books I read on marketing, self-improvement, productivity, personal finance, and mindfulness grew steadily.

However, the notes, underlined sentences, and comments written in the margins of the paper were nothing like the notes I took in my university classes.

There was one important difference between the two:

This time I wanted to use the knowledge I had acquired.

I wanted to remember the lessons, to work on the ideas I had come up with while reading. Once I started blogging it became important to find an anecdote illustrating the idea of an article in my notes. To do that, I needed to have good notes.

For two years I have been trying to develop the perfect note-taking system, which you can follow on the blog. I tried countless apps (Evernote, Roam Research, Notion). I have tried different learning methodologies and note-taking techniques (mind-maps, Cornell method).

Each one was a small step towards smart note-taking, but the breakthrough was not until I discovered the Zettelkasten method.

I realized that note-taking has a much bigger role to play in the success of those living and working as a knowledge worker than I had first thought.

It was not my notes, but my thinking that was transformed by a radically different approach to note-taking, which I had tried simply to take better notes.

This new approach is the Zettelkasten method, which has helped me to notice the following positive changes:

- The blank pages have disappeared. If you're working on a task with a well-defined end product, such as a submission, essay, thesis, a short story, or the script of your YouTube video, you're familiar with the blank page syndrome. You need to write. You make yourself do it, sit down at your desk and then freeze, staring at the blank paper. Then you gather resources at best, procrastinate at worst. With the Zettelkasten method, blank sheets are eliminated. I have ideas, stories, and references on paper when I start writing.

- All my ideas are in one place. While reading, I used to concentrate so much on the text that I would let my thoughts loosely related to the book drift away. But sometimes one idea is worth more than the whole book. In the same way, I didn't know what to do with the ideas that came to me during buffer time (walking, washing up, showering). Zettelkasten made me aware of the role and place of these ideas.

- I have a better understanding of what I read. Highlighting and underlining don't work because we don't work with the text. We store the ideas someone else has put in our short-term memory. I use Zettelkasten to regurgitate the author's sentences and translate them into my own words.

- I don't stop at superficial questions. Because the Zettelkasten method forces me to interpret the topic of the note, I ask better questions. The search for answers leads to more questions. And thanks to more and better research, my previous notes and articles seem confusingly superficial compared to Zettelkasten-based content.

If you're an undergraduate writing a thesis, a marketer composing gripping stories to avoid the panic of blank pages, or if you want to better understand the context behind things, or simply want better ideas, the Zettelkasten method will be useful to you.

In the following, I will explain the basics of the Zettelkasten method and the steps to implement it.

What is the Zettelkasten method?

Zettelkasten is a method for managing knowledge, a note-taking system that focuses on linked ideas.

Niklas Luhmann's slip box

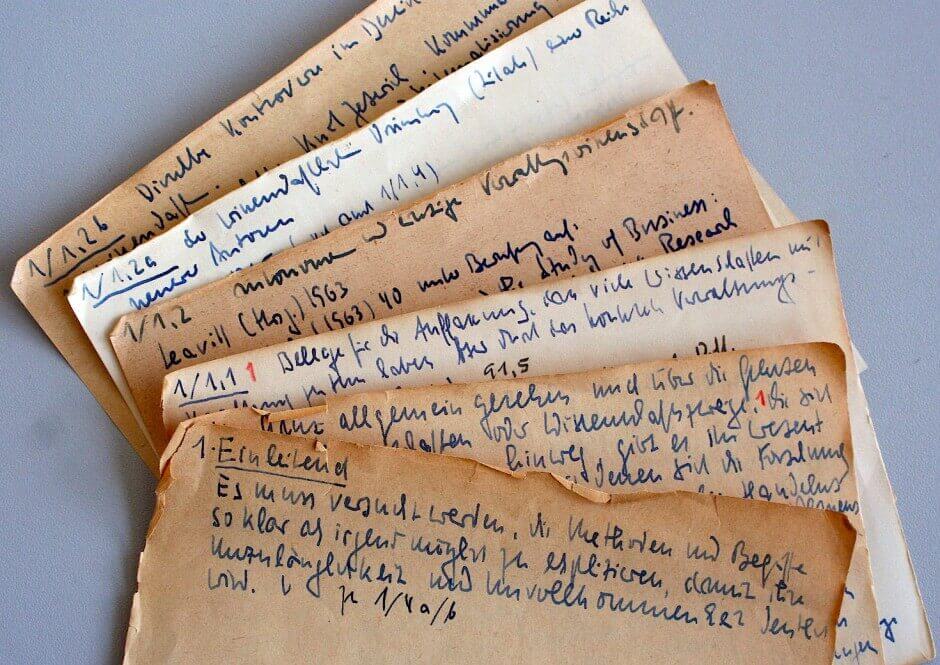

The slip box is named after the German social scientist Niklas Luhmann. After years of writing notes in the margins of books, and collecting them thematically, Luhmann realized that this note-taking was going nowhere. So he turned his previous system upside down.

Instead of putting his notes into existing categories, he wrote a number in the corner of his note cards to indicate the relationship between the notes. He then collected these cards in a box in the order of the numbers. Hence the name of the method.

While many academics try to write as many papers and books as possible from a single idea, Luhmann seems to have done the opposite. He generated more ideas than he could write about thanks to his notes.

During his lifetime, Luhmann wrote 70 books and more than 400 scientific articles.

In addition to law, political science, religion, and economics, he has written on mass communication and the media.

Luhmann not only made better notes, he thought inside the slip box. He used his notes to generate ideas, better understand concepts and think. In addition to its positive impact on productivity, Luhmann highlights another advantage of the Zettelkasten Method.

He says he never worked on a topic he didn't feel like working on. He took the lack of motivation as natural feedback and instead of forcing himself to work on a topic, he would look for a more interesting idea in his slip box that he felt like doing.

The problem with traditional note-taking

Whatever topic we want to write about, we cannot predict the outcome of our research. The problem with traditional note-taking (and with theses, dissertations, and most academic work) is that it forces you into a structure that inhibits thinking.

You need to formulate a hypothesis before you start researching.

List bibliography while the best sources are found during research.

Forcing research into a rigid structure, setting goals in advance about the purpose of the article, and reading and writing according to them is not only demotivating, but it is also inefficient.

Research is an open-ended process, as is note-taking.

Build the structure as you go, from the bottom up!

Don't create categories and labels in advance and then shove ideas into them.

Connect the ideas that fit together as you go!

The idea generator

Luhmann had two different slip boxes.

In one he kept bibliographical references, the location of the book chapters that supported his ideas, while in the main slip box he recorded his ideas. He separated the reading from the reaction in his head but referred to the passage. He wrote his notes on index cards and stored them in wooden boxes.

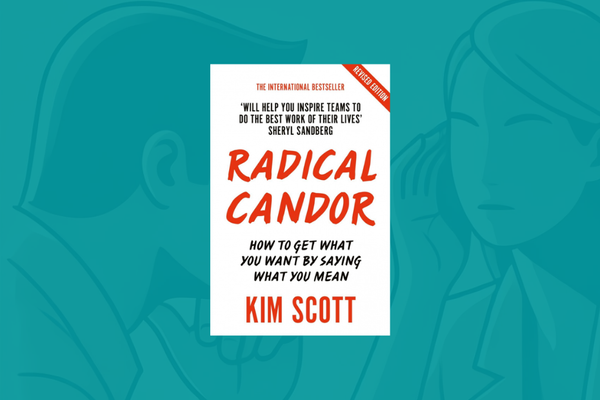

In his book How to take smart notes, Sönke Ahrens translates Luhmann's zettelkasten method into a digital environment. He proposes separate programs for managing references and generating ideas.

But a few years have passed since the book was published.

New softwares have appeared on the horizon that are intended to implement the concept of linked ideas. Whereas in the past you had to put together a well-functioning Zettelkasten system, today much more user-friendly solutions are available.

The idea generator and the links can now be combined in one program.

Tools like Roam Research, Obsidian, TiddlyWiki have made the Zettelkasten method easy to use. And thanks to the communities built around the software, there are countless tutorials and videos of personal Zettelkasten accounts (#roamtour) on the web.

But how do we start building our own Zettelkasten system?

Zettelkasten workflow for beginners

Sönke Ahrens, who demonstrates the practical application of the Zettelkasten method, proposes three different types of notes, modeled on Luhmann:

- Fleeting notes: ideas, scratchings that you can jot down without any particular system or structure. These notes should not be immediately categorized or given a purpose. They either become permanent notes within a few days or end up in the trash.

- Permanent notes: They contain the information needed to understand the concept without context. A permanent note requires a no-frills interpretation of the topic and a way of putting the phenomenon in your own words.

- Project notes: Notes made specifically for a project that might not otherwise have a place in the note box. For example, bestselling author Ryan Holiday has created each of his books using a different slip box but does not reuse each box for future reference. He organizes these notes into individual folders and archives them at the end of the project.

Closely linked to the different types of notes are Ahrens' practical tips for using the Zettelkasten method:

- Make fleeting notes!

- Make literature notes!

- Make permanent notes!

- Put your permanent notes in the box!

- Work out your ideas from the bottom up using the slip box!

- Choose the topics you want to write about from the outline.

- Shrink your existing notes into a first draft!

- Edit and proofread the final result!

1. Make fleeting notes!

The purpose of a memo is to jot down ideas that come to mind. There is no need to force these ideas into a system. Their purpose is merely to document, to preserve ideas, and to allow you to turn them into permanent notes.

2. Take literature notes!

For many of us, what Ahrens calls the literature note is note-taking by itself, but these notes are merely the support for the ideas. Luhmann never underlined sentences or wrote comments in the margins of the book.

He merely noted down the ideas that came to his mind while reading and wrote a bibliographical reference (book-page-sequence).

Verbatim quotations should be avoided.

Out-of-context sentences change meaning once taken out of context, even if the words themselves do not change.

3. Make permanent notes!

Write down your ideas, referring to the text that supports the idea. The next step is to interpret the idea you have written down.

If you express an idea in the words of others and use it in only one context, you probably don't understand the point yet. Think enough about your fleeting note to be able to express it in your own words!

What does the subject of the fleeting note mean in another context? Can you use the idea in a completely different situation/industry/age?

Permanent notes should point beyond the text you read, beyond the author's thoughts.

4. Put your permanent notes in the box!

Luhmann placed his related notes one behind the other in his slip box. Even if you prefer a digital note box, it is still worth marking the links between the notes.

This could be a two-way link, a unique number, or an index.

Although note-taking based on labels and categories is not efficient, keywords can be useful for finding links between mature ideas.

You can add keywords to your permanent notes to serve as an entry point for later and link similar notes.

5. Work out your ideas from the bottom up using the slip box!

The greatest value of the slip box is that it helps you think inside the box. Notes highlight connections, raise new questions, and ultimately encourage you to work through complex issues in detail.

Rather than formulating the topic of an article or research project in advance, it is worth following the notes and defining directions along the way!

6. From the topics that emerge, choose the one you want to write about!

If you settle for better ideas and a network of connected thoughts, the Zettelkasten method ends for you after the fifth point. However, if you want to create something new, to express the end product of your thinking in a rounded body of content, then it's worth choosing a topic already outlined by the connections between the notes, in which you can immerse yourself even more.

7. Collect your existing notes into a first draft!

If you follow the Zettelkasten method, you won't be received by a blank piece of paper before writing your article, but you will be able to use the links between your notes to pick up ideas and stories relevant to your topic.

The writing won't necessarily be writing but organizing your thoughts into a logical outline.

8. Edit and proofread the final result!

Finally, this outline should be edited into an understandable text.

Suggestions for using the Zettelkasten method

Although I've been building my own digital note box for months, I'm still a beginner at it. After a bit of searching, the notes universe can open up to you and you can find content that goes well beyond the scope of this article, surpassing my template points in complexity.

I suggest a few tools and resources that have helped me in particular:

Zettelkasten softwares

- Roam Research (a pioneering software with a wide audience but with a paid app)

- Obsidian (a Zettelkasten alternative that you can host on your own computer)

- Notion (with the new backlink feature, they have enabled two-way linking)

- RemNote

- TiddlyWiki

- Foam